Competence is difficult to define and even harder to measure. That is what Benjamin Wooster, MD, an orthopaedic surgery resident at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, learned when he undertook a study to determine if anatomic knowledge correlates with surgical competence as part of his ABMS Visiting Scholar research project.

“Patients want to know if the surgeon who is going to operate on them is competent to do so,” said Dr. Wooster, who is in the 2015-16 class of ABMS Visiting Scholars. “And residency programs need to be able to determine if graduates are truly competent at the end of their training.” The primary goal of his project was to develop a tool that can assess competence of orthopaedic surgery residents in a more objective manner than current assessment tools.

Current competence measures rely on the observations and subjective assessments of the trainee by the program director, faculty members, and peers, explained Dr. Wooster, who was sponsored by the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery (ABOS). The determination of competence is supported by periodic program-specific testing, annual in-training examinations, and the successful completion of a specialty board examination. However, even cases submitted for the Part II Examination of the ABOS’ Board Certification process are subjectively evaluated, he said.

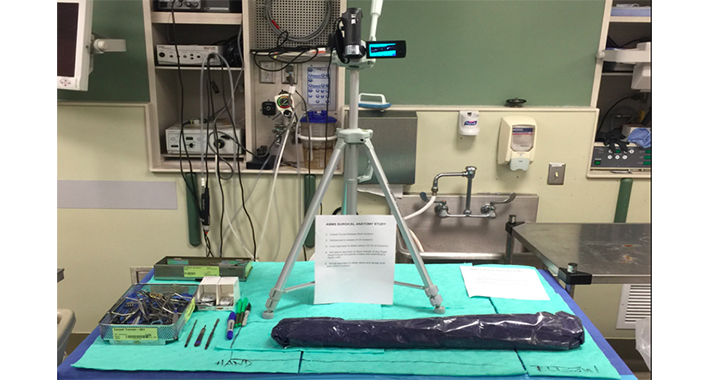

For his research project, Dr. Wooster evaluated the anatomic knowledge base of orthopaedic surgery trainees performing two common upper extremity procedures (carpal tunnel release and the volar approach to the distal radius). The procedures were performed and videotaped in a simulated surgical setting using cadavers. Trainees were instructed to speak to the video, providing as much anatomic knowledge pertinent to the procedure and the condition as possible. Minimum standards for anatomic knowledge were established from the results of a survey sent to all directors of hand surgery fellowships across the United States. Each video was then evaluated by the study authors using a standardized grading system. Surgical assessments of 29 orthopaedic surgery trainees from Duke University and the Harvard Combined Orthopaedic Residency Program were performed at the beginning and end of the academic year. Dr. Wooster then compared the residents’ anatomic knowledge with clinical competence ratings obtained from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Orthopaedic Surgery Milestones.

As a group, residents demonstrated a significant progression in anatomic knowledge each post-graduate year based on the objective assessment tool. Although a trend toward improvement in individual trainee’s anatomic knowledge over the course of one academic year was observed, the gains were not statistically significant. “These findings suggest that surgical competency is a graduated process involving repeated exposure to concepts and procedures throughout residency training,” Dr. Wooster said. Improvement in Milestone scores also occurred each year, however, the variation between junior and senior orthopedic surgery residents was small and trainees at all levels scored above 4 (out of 5). These data raise the question as to whether the current subjective application of the Milestones system is able to accurately assess surgical competence. “The relative lack of objectivity and standardization of the Milestones may restrict accurate reporting of resident competence and limit the benefits of summative and formative feedback for trainees,” he added.

The search for an objective competence assessment tool by Dr. Wooster and his colleagues is associated with the development of a competency-based curriculum in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Duke University. The program is establishing a curriculum that highlights the core competencies for a general orthopaedic surgeon over the first three years, providing opportunities for selective rotations and areas of progressive clinical responsibilities in the fourth and fifth years of residency training. “Defining core content, providing opportunities to apply core knowledge and core skills through simulation and clinical experiences, and evaluating competencies have been the primary areas of development,” he said. “Adult learning techniques, such as case-based and interactive learning sessions and formative feedback, will be critical to a more efficient learning environment.”

As time, clinical case volume, and clinical exposure remain independent factors that influence the development of surgical technical, diagnostic, and decision-making skills, it is essential that surgical education involves a process that helps to identify areas for improvement and confirms various competencies.

While the study does not confirm whether knowing a certain percentage of anatomic facts correlate with an orthopaedic surgery resident’s specific level of competence, Dr. Wooster believes that the objectivity of the scoring system provides opportunities for confirmation as to a basic fund of knowledge critical to both comprehension of the condition and to the surgical procedure; a review of knowledge gaps for education development and for an individual’s education strategy; and charting progress of an individual or group relative to training level expectations.

Although Dr. Wooster acknowledges that it’s tough to have complete objectivity, the more objective the assessment tool, the better it will serve residents, program directors, and patients alike. “Surgical competence is difficult to objectively measure, but it’s important that we attempt to shift the evaluation process toward more objective measures, without ignoring the importance of subjective appreciation for the educational review process,” he said. The accurate assessment of competence will require continued innovation (and even some objective validation) and Dr. Wooster hopes that his Visiting Scholars research project will inspire continued development of this important concept.